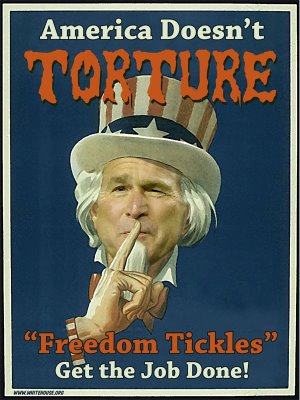

The case for separation of church and state has never been better made than it has in the United States over the past six years. Canada is now being dragged down into "faith based" government and we won't be happy with the results if we let this carry on.

GeorgeBush's rule is nothing if not faith based. This infinitely peculiar man believes that God acts through him. In other words, Little Georgie's decisions are actually a manifestation of God's will. Who needs reason, what possible place can there be for logic, or debate, or considered analysis, when one's very instincts are divine?

I suspect that the American President actually believes this nonsense. His actions and words certainly support that conclusion. His Messianic belief is evident in the string of colossal failures that have flowed from The Decider's decisions and, yes, the capitalization was intentional.

In October, 2004, author Ron Suskind wrote an article, "Faith, Certainty and the Presidency of George W. Bush" that appeared in the New York Times Magazine. The excerpts that follow are or should be required reading:

"Joe Biden was telling a story, a story about the president. ''I was in the Oval Office a few months after we swept into Baghdad,'' he began, ''and I was telling the president of my many concerns'' -- concerns about growing problems winning the peace, the explosive mix of Shiite and Sunni, the disbanding of the Iraqi Army and problems securing the oil fields. Bush, Biden recalled, just looked at him, unflappably sure that the United States was on the right course and that all was well. '''Mr. President,' I finally said, 'How can you be so sure when you know you don't know the facts?'''

"Biden said that Bush stood up and put his hand on the senator's shoulder. ''My instincts,'' he said. ''My instincts.''

"The Delaware senator was, in fact, hearing what Bush's top deputies -- from cabinet members like Paul O'Neill, Christine Todd Whitman and Colin Powell to generals fighting in Iraq -- have been told for years when they requested explanations for many of the president's decisions, policies that often seemed to collide with accepted facts. The president would say that he relied on his ''gut'' or his ''instinct'' to guide the ship of state, and then he ''prayed over it.'' The old pro Bartlett, a deliberative, fact-based wonk, is finally hearing a tune that has been hummed quietly by evangelicals (so as not to trouble the secular) for years as they gazed upon President George W. Bush. This evangelical group -- the core of the energetic ''base'' that may well usher Bush to victory -- believes that their leader is a messenger from God. And in the first presidential debate, many Americans heard the discursive John Kerry succinctly raise, for the first time, the issue of Bush's certainty -- the issue being, as Kerry put it, that ''you can be certain and be wrong.''

"What underlies Bush's certainty? And can it be assessed in the temporal realm of informed consent?

"All of this -- the ''gut'' and ''instincts,'' the certainty and religiosity -connects to a single word, ''faith,'' and faith asserts its hold ever more on debates in this country and abroad. That a deep Christian faith illuminated the personal journey of George W. Bush is common knowledge. But faith has also shaped his presidency in profound, nonreligious ways. The president has demanded unquestioning faith from his followers, his staff, his senior aides and his kindred in the Republican Party. Once he makes a decision -- often swiftly, based on a creed or moral position -- he expects complete faith in its rightness.

"Some officials, elected or otherwise, with whom I have spoken with left meetings in the Oval Office concerned that the president was struggling with the demands of the job. Others focused on Bush's substantial interpersonal gifts as a compensation for his perceived lack of broader capabilities. Still others, like Senator Carl Levin of Michigan, a Democrat, are worried about something other than his native intelligence. ''He's plenty smart enough to do the job,'' Levin said. ''It's his lack of curiosity about complex issues which troubles me.'' But more than anything else, I heard expressions of awe at the president's preternatural certainty and wonderment about its source.

"Looking back at the months directly following 9/11, virtually every leading military analyst seems to believe that rather than using Afghan proxies, we should have used more American troops, deployed more quickly, to pursue Osama bin Laden in the mountains of Tora Bora. Many have also been critical of the president's handling of Saudi Arabia, home to 15 of the 19 hijackers; despite Bush's setting goals in the so-called ''financial war on terror,'' the Saudis failed to cooperate with American officials in hunting for the financial sources of terror. Still, the nation wanted bold action and was delighted to get it. Bush's approval rating approached 90 percent. Meanwhile, the executive's balance between analysis and resolution, between contemplation and action, was being tipped by the pull of righteous faith.

"It was during a press conference on Sept. 16, in response to a question about homeland security efforts infringing on civil rights, that Bush first used the telltale word ''crusade'' in public. ''This is a new kind of -- a new kind of evil,'' he said. ''And we understand. And the American people are beginning to understand. This crusade, this war on terrorism is going to take a while.''

"Muslims around the world were incensed. Two days later, Ari Fleischer tried to perform damage control. ''I think what the president was saying was -- had no intended consequences for anybody, Muslim or otherwise, other than to say that this is a broad cause that he is calling on America and the nations around the world to join.'' As to ''any connotations that would upset any of our partners, or anybody else in the world, the president would regret if anything like that was conveyed.''

"A few months later, on Feb. 1, 2002, Jim Wallis of the Sojourners stood in the Roosevelt Room for the introduction of Jim Towey as head of the president's faith-based and community initiative. John DiIulio, the original head, had left the job feeling that the initiative was not about ''compassionate conservatism,'' as originally promised, but rather a political giveaway to the Christian right, a way to consolidate and energize that part of the base.

"Moments after the ceremony, Bush saw Wallis. He bounded over and grabbed the cheeks of his face, one in each hand, and squeezed. ''Jim, how ya doin', how ya doin'!'' he exclaimed. Wallis was taken aback. Bush excitedly said that his massage therapist had given him Wallis's book, ''Faith Works.'' His joy at seeing Wallis, as Wallis and others remember it, was palpable -- a president, wrestling with faith and its role at a time of peril, seeing that rare bird: an independent counselor. Wallis recalls telling Bush he was doing fine, '''but in the State of the Union address a few days before, you said that unless we devote all our energies, our focus, our resources on this war on terrorism, we're going to lose.' I said, 'Mr. President, if we don't devote our energy, our focus and our time on also overcoming global poverty and desperation, we will lose not only the war on poverty, but we'll lose the war on terrorism.'''

"Bush replied that that was why America needed the leadership of Wallis and other members of the clergy.

''No, Mr. President,'' Wallis says he told Bush, ''We need your leadership on this question, and all of us will then commit to support you. Unless we drain the swamp of injustice in which the mosquitoes of terrorism breed, we'll never defeat the threat of terrorism.''

"Bush looked quizzically at the minister, Wallis recalls. They never spoke again after that.

"In the summer of 2002, after I had written an article in Esquire that the White House didn't like about Bush's former communications director, Karen Hughes, I had a meeting with a senior adviser to Bush. He expressed the White House's displeasure, and then he told me something that at the time I didn't fully comprehend -- but which I now believe gets to the very heart of the Bush presidency.

"The aide said that guys like me were ''in what we call the reality-based community,'' which he defined as people who ''believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality.'' I nodded and murmured something about enlightenment principles and empiricism. He cut me off. ''That's not the way the world really works anymore,'' he continued. ''We're an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you're studying that reality -- judiciously, as you will -- we'll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that's how things will sort out. We're history's actors . . . and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do.''

"Can the unfinished American experiment in self-governance -- sputtering on the watery fuel of illusion and assertion -- deal with something as nuanced as the subtleties of one man's faith? What, after all, is the nature of the particular conversation the president feels he has with God -- a colloquy upon which the world now precariously turns?

"That very issue is what Jim Wallis wishes he could sit and talk about with George W. Bush. That's impossible now, he says. He is no longer invited to the White House.

''Faith can cut in so many ways,'' he said. ''If you're penitent and not triumphal, it can move us to repentance and accountability and help us reach for something higher than ourselves. That can be a powerful thing, a thing that moves us beyond politics as usual, like Martin Luther King did. But when it's designed to certify our righteousness -- that can be a dangerous thing. Then it pushes self-criticism aside. There's no reflection.

''Where people often get lost is on this very point,'' he said after a moment of thought. ''Real faith, you see, leads us to deeper reflection and not -- not ever -- to the thing we as humans so very much want.''

"And what is that?

''Easy certainty.''

How much Bush is there in our own Stephen Harper? There are similarities between the two men but, to be sure, there are also key differences. Some, perhaps, reflect different circumstances: Stephen Harper sits as prime minister but his grasp on power is much more tenuous. He leads a very thin minority government and a nation that isn't nearly as strongly in the grip of the religious right, at least not yet. Change, however, is very much afoot in Ottawa.

The arrival of Harper at 24 Sussex Drive brought a flock of Christian fundamentalists to Ottawa. It doesn't matter that two-thirds of Canadian voters didn't back their guy, they mean to make hay while the sun shines. They had better move fast and they know it.

I'll expand on this subject in the coming days. In the meantime, if you want to learn more, see if you can lay your hands on a copy of the Focus section of Saturday's Globe and Mail or buy the October edition of The Walrus, available at news stands now.