America didn't get where it is today overnight. It took the better part of 60-years. Writing in Harper's, Rebecca Solnit traces how the "Tyranny of the Minority" came to be.

The dismantling started in the 1960s, when the two main parties reversed positions on civil rights. Lyndon Johnson led the Democrats toward stronger alliances with people of color and with women. The Republicans, meanwhile, won the South with the Southern Strategy, that euphemistically named program to gain the support of white Southerners by stoking their racial fears. Justification for the approach had been offered years earlier by William F. Buckley Jr. “The White community in the South is entitled to take such measures as are necessary to prevail, politically and culturally, in areas in which it does not predominate numerically,” Buckley wrote in 1957. “For the time being, it is the advanced race.” On the basis of that “advanced” status, Buckley decided, a decision to wrest control from the majority “may be, though undemocratic, enlightened.” At its most ideological, the withdrawal from the democratic experiment has served white supremacy; at its least, it has been a scramble for power by any means necessary. Even as the civil-rights movement and the Voting Rights Act sought to undo Jim Crow, a new, stealthier Jim Crow arose in its place.

Writing in The New Republic, the journalist Jeet Heer explains that Buckley’s fledgling conservative movement recognized that by persuading disgruntled whites across the country to vote according to their racial and ideological rather than economic interests, it could gain “reliable foot soldiers” in its larger project of undermining the left. In wooing white voters, Republicans rejected — indeed, ejected — non-white constituencies, who found their only and imperfect home with the Democrats. And where Democrats have been wavering and inconsistent in their desire to expand democratic participation, Republicans have been firmly committed to limiting it: rather than attempting to win the votes of people of color, they attempt to prevent people of color from voting.

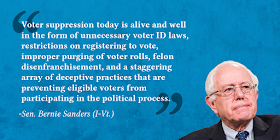

Republicans’ furious and nasty war against full participation has taken many forms: gerrymandering, limiting early voting, reducing the number of polling places, restricting third-party voter registration, and otherwise disenfranchising significant portions of the electorate. Subtler yet no less effective have been their efforts to attack democracy at the root. They have advanced policies to weaken the electorate economically, to undermine a free and fair news media, and to withhold the education and informed discussion that would equip citizens for active engagement. In 1987, for example, Republican appointees eliminated the rule that required radio and TV stations to air a range of political views. The move helped make possible the rise of right-wing talk radio and of Fox News, which for twenty years has effectively served the Republican Party as a powerful propaganda arm.

...

Some Republicans have argued for a more inclusive approach, but they are not leading the way. The party isn’t changing its strategy in order to win a majority; it is intensifying its efforts to suppress that majority. It has committed itself to minority rule. As the non-white population swells, Republican scenarios for holding power will look more and more like those of apartheid-era South Africa — or even the antebellum South. Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III, Trump’s nominee for attorney general, is infamous for his efforts in the 1980s to persecute black voting-rights activists and intimidate hundreds of black voters. In the next decade, either the Party of Lincoln will force us to backtrack for decades, perhaps a century, or we will overcome its obstructionism and walk forward. If anything redeems this nation, it’s the idealism that has for centuries moved abolitionists, suffragists, Freedom Riders, and their like to stand up for the country’s principles — to risk, sometimes, their lives. Hundreds of activist groups have formed in the wake of the election, beginning projects to register voters, renew voting-rights campaigns, and organize local power to influence national policy. The NAACP’s Barber calls this era the Third Reconstruction.

Voter suppression is a problem but it pales in comparison to high rates of voluntary non-participation in sections of the American electorate. I disagree with the author's assertion that the Republican party is the principal enemy of those who don't participate. If the author thinks they are the enemy, then explain how California and Hawaii have low voter participation rates? Also, the author decries the lack of balance on radio. This is true. Yet in the last election the print media in even Republican states, like Texas, were endorsing Clinton. If voters are fooled about, or unaware of, the real positions of the Democrats and Republicans, it isn't because of a lack of media diversity. And when the Dems held Michigan, did they fix the poor voting machine problems?

ReplyDeleteThe U.S. left, in the form of the Democratic party, has done little to fix their voting problem over the last few decades. There's a show of angst for a few months post-election, but they don't follow through with a coordinated effort to change participation rates by a combination of appealing to voters through policy and get-out-the-vote campaigning. In competitive states, they lose at the federal level, the state level, and even the municipal level because they don't have targeted, appealing policies, don't help people get registered and do not get out their registered voters to the polls. Suppression is a problem, but the Ds often losing is not because their voters are "suppressed".